Vietnamese Confucianism is more than just a set of philosophical teachings—it is a foundational element of Vietnam’s social, cultural, and political life. Introduced during the Chinese domination period and later adopted as the ruling ideology under various Vietnamese dynasties, Confucianism helped shape values like respect for hierarchy, filial piety, moral integrity, and education. Today, the legacy of Vietnamese Confucianism can still be seen in family structures, educational traditions, and the way Vietnamese people approach social relationships and personal conduct.

What Is Vietnamese Confucianism?

Vietnamese Confucianism is a uniquely localized adaptation of Confucian philosophy, which originated in China during the 6th century BCE. Over a millennium of cultural contact with China led Vietnam to absorb, modify, and apply Confucian ideals within its own cultural, political, and social frameworks. The result was not a simple copy of Chinese Confucianism, but a hybrid system deeply intertwined with Vietnamese values, indigenous customs, Buddhism, Taoism, and the lived experiences of its people.

Understanding Vietnamese Confucianism provides insight into how Vietnamese culture evolved, how the state was governed, how families functioned, and why education remains a sacred value in Vietnam today.

1. Historical Development of Vietnamese Confucianism

1.1 Early Introduction (1st Century BCE – 10th Century CE)

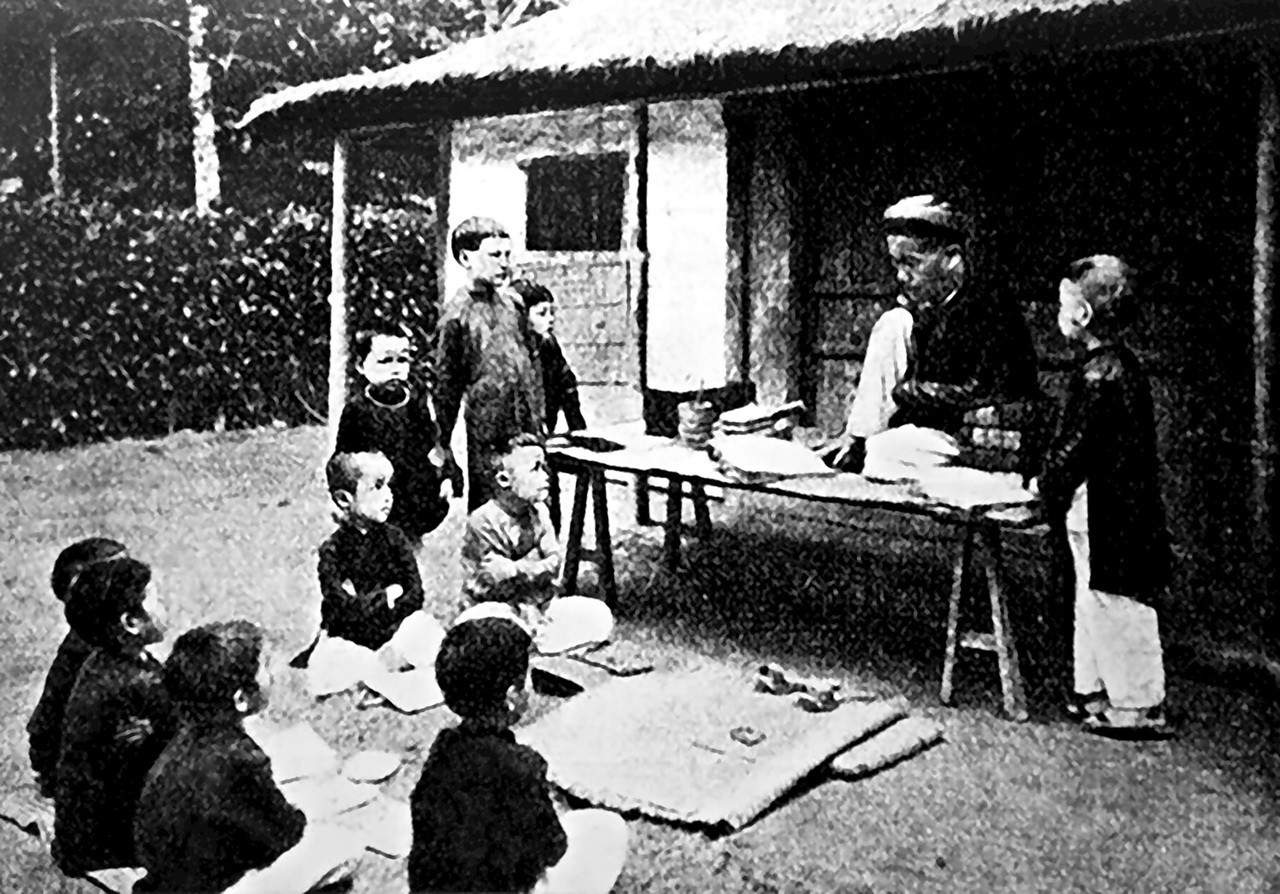

Confucianism first entered Vietnam during Chinese imperial rule (111 BCE – 939 CE). It was mainly propagated by Chinese governors and scholars, such as Sĩ Nhiếp, who established early Confucian schools. However, it failed to reach the broader Vietnamese population, who remained attached to ancestral worship, animism, and later Buddhism.

Confucianism during this time served colonial administrative functions rather than local cultural integration.

1.2 Rise During Independent Dynasties (11th – 14th Century)

After gaining independence, Vietnamese rulers began adopting Confucian principles to build and legitimize their governments. King Lý Thánh Tông (r. 1054–1072) established the Temple of Literature (Văn Miếu) in Hanoi in 1070, marking the beginning of Confucianism’s institutional role in Vietnamese society.

Despite this progress, Buddhism remained dominant among the people, while Confucianism was mainly confined to state administration and elite scholars.

1.3 The Golden Age: Lê Dynasty (15th Century)

Vietnamese Confucianism reached its peak under the Lê Dynasty (1428–1527). It became the state ideology, shaping governance, education, and social behavior. Civil service examinations based on Confucian classics were formalized, and Confucian morality became embedded in laws and public policy.

Vietnam became a truly Confucian nation — in structure, law, and thought — but still retained significant Buddhist and folk influences at the grassroots level.

1.4 Confucianism Under the Nguyễn Dynasty (1802–1945)

Under the Nguyễn Dynasty, Vietnamese Confucianism maintained a dominant role but became increasingly rigid, ceremonial, and resistant to reform. While emperors like Gia Long and Minh Mạng sought to consolidate power using Confucian principles, this also prevented modernization, making the country vulnerable to colonial exploitation.

2. Core Values of Vietnamese Confucianism

2.1 Filial Piety (Hiếu)

Filial piety is the most central virtue in Vietnamese Confucianism. It goes beyond honoring parents — it includes ancestral worship, family loyalty, and passing down family traditions.

This virtue helped shape Vietnam’s strong family systems, where multi-generational households and respect for elders remain the norm.

2.2 Loyalty to the State (Trung quân ái quốc)

Confucianism teaches loyalty to one’s ruler as essential to societal order. In Vietnam, this became loyalty to the nation, especially during times of war or foreign invasion. The term “trung” (loyalty) took on nationalist meanings during colonial resistance, allowing Confucianism to blend into Vietnam’s patriotic movements.

2.3 Education and Meritocracy

Confucianism regards learning as a moral duty. Vietnamese Confucianism placed tremendous value on education, leading to the creation of a literati class — nho sĩ — whose influence shaped Vietnamese scholarship and literature.

This legacy is why Vietnam has one of the highest literacy rates in Southeast Asia today, and why education continues to be revered as a path to success and virtue.

2.4 Social Harmony and Hierarchy

Confucianism promotes social harmony through defined relationships: ruler–subject, father–son, husband–wife, elder–younger, and friend–friend. Vietnamese Confucianism mirrored these, often combining them with village customs and Buddhist compassion to create a balanced social ethos.

3. Vietnamese Confucianism and the Education System

From the 11th century until 1919, Confucian examinations were the official means of selecting civil servants. These exams tested knowledge of Confucian classics, moral reasoning, and rhetorical skill. Success granted titles like Tiến sĩ (Doctor) or Trạng nguyên (Top Scholar), opening the door to government positions.

Notable Confucian scholars of Vietnam include:

- Nguyễn Trãi – strategist, poet, and national hero

- Ngô Sĩ Liên – author of Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư (Complete History of Đại Việt)

- Nguyễn Bỉnh Khiêm – a prophetic scholar and adviser

- Lê Quý Đôn – philosopher and encyclopedist

These scholars preserved Vietnamese history, ethics, and literature, and continue to inspire modern thought.

4. Vietnamese Confucianism and Cultural Practices

4.1 Family and Gender Roles

While Confucianism promoted family cohesion, it also enforced patriarchal systems. Women were expected to follow Tam Tòng Tứ Đức — obey father, husband, then son; and cultivate four virtues: work, appearance, speech, and morality.

These ideals restricted women’s freedom for centuries. However, Vietnamese folk literature and figures like poet Hồ Xuân Hương pushed back, introducing themes of female autonomy and social satire.

4.2 Village Governance

Confucianism did not fully penetrate rural village life. There, local customs often overruled imperial edicts, summarized by the Vietnamese saying: “Phép vua thua lệ làng” (The king’s law yields to village customs). This coexistence illustrates how Vietnamese Confucianism adapted to real-life community needs rather than imposing abstract doctrine.

5. Architecture and Confucian Landmarks

Many Confucian sites still exist and can be visited today:

5.1 Temple of Literature (Văn Miếu – Quốc Tử Giám) – Hanoi

- Built in 1070 to honor Confucius

- Vietnam’s first national university

- Features stone steles listing the names of Confucian scholars who passed royal exams

5.2 Phu Văn Lâu (Hue)

- Erected during the Nguyễn dynasty

- Used for public proclamations and imperial edicts

- Represents the integration of Confucianism into royal governance

5.3 Regional Confucian Temples

Other provinces like Bắc Ninh, Hải Dương, and Hưng Yên have their own Confucian shrines and examination relics, though many need restoration. These sites form a potential network for Confucian heritage tourism in Vietnam.

6. The Decline of Vietnamese Confucianism

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Vietnamese Confucianism began to wane due to several factors:

- French colonialism introduced secular education

- Abolition of the Confucian exam system in 1919

- Rise of modern nationalism, socialism, and democracy

- Exposure to Western science and philosophy

Many reformers and revolutionaries — including Phan Bội Châu, Phan Châu Trinh, and Nguyễn Đình Chiểu — began as Confucian scholars but abandoned orthodoxy to pursue national liberation.

7. Vietnamese Confucianism in Modern Times

Though no longer an official ideology, Confucianism still influences Vietnamese culture today:

7.1 Respect for Education

Vietnamese parents prioritize education, viewing it as both a moral duty and a path to upward mobility — a clear legacy of Confucian values.

7.2 Family Values

Modern families still practice ancestor worship, maintain extended family ties, and uphold respect for elders — all rooted in Confucian teachings.

7.3 Public Morality

Concepts like “nhân” (benevolence), “nghĩa” (righteousness), and “lễ” (propriety) influence personal conduct and community expectations.

However, these values have also been modernized and reframed through socialist and nationalist lenses. For example, “Trung với nước, hiếu với dân” (Loyal to the country, filial to the people) is a modern reinterpretation of ancient Confucian virtues.

8. Criticisms and Contemporary Debates

Some modern scholars and feminists critique Confucianism for:

- Reinforcing gender inequality

- Inhibiting critical thinking

- Valuing conformity over creativity

However, others argue that Vietnamese Confucianism, having been shaped by local culture and softened by Buddhism, is not as rigid or oppressive as its Chinese counterpart.

The future of Vietnamese Confucianism may lie in its selective integration into modern values — preserving ethical standards while promoting equality, creativity, and progress.

Conclusion: A Philosophy Adapted, Not Imposed

Vietnamese Confucianism stands as a powerful example of how imported ideologies are localized, adapted, and transformed. It helped Vietnam build a strong civil society, a literate bureaucracy, and a cohesive cultural identity.

Today, Confucian values continue to live quietly beneath the surface — in classrooms, family homes, and national attitudes — serving as a moral compass for generations past and present.

For travelers, scholars, and cultural enthusiasts, understanding Vietnamese Confucianism is key to understanding Vietnamese identity itself with Vietnam Culture.

See more post: Vietnamese Buddhist traditions: A deep dive into Vietnam’s living spiritual heritage